TRAILS OF STRUGGLE

The Vietnam War: A Turning Point

for Black American Rights

“President Harry S. Truman Shakes Hands with African American Air Force Sergeant.” October 12, 1950. Retrieved from the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library & Museum

"Herein lie buried many things which if read with patience may show the strange meaning of being black here at the dawning of the Twentieth Century. This meaning is not without interest to you, Gentle Reader; for the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line." Sociologist W.E.B. Dubois

For generations, the United States Armed Forces remained segregated.

During the Civil War, about 180,000 men served in the Union Army in support roles (National Archives). Thousands of others were coerced into Confederate service under General Orders No. 14, which maintained the status quo of slavery despite forced Black confederate involvement (Virginia Museum of History & Culture).

"That, in order to provide additional forces to repel invasion, maintain the rightful possession of the Confederate States, secure their independence, and preserve their institutions, the President be, and he is hereby, authorized to ask for and accept from the owners of slaves, the services of such number of able-bodied negro men as he may deem expedient, for and during the war, to perform military service in whatever capacity he may direct." General Orders No. 14, Section 1, 1865.

"That nothing in this act shall be construed to authorize a change in the relation which the said slaves shall bear toward their owners, except by consent of the owners and of the States in which they may reside, and in pursuance of the laws thereof." General Orders No. 14, Section 3, 1865.

Timothy H. O'Sullivan. “Fredericksburg, Virginia. Burial of Federal dead.” May 20, 1864. Retrieved from the Library of Congress

"They were in service positions; they were mostly put in positions to do the grunt work... It's also important to understand that even though it was segregated, it wasn't equal. Black soldiers were receiving inadequate training and resources." Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Professor of African-American history at Ohio State University

An Uneven Playing Field

During WWI and WWII, nearly 400,000 and over 1,000,000 Black Americans served respectively, but they disproportionately received blue discharges, barring them from the same veteran benefits afforded to white peers (National Archives). After WWII, Black Americans faced violent discrimination and were denied equal job opportunities, sparked by white “nervousness and fear” of social equality.

“At the heart of it was a kind of nervousness and fear that many whites had that returning Black veterans would upset the racial status quo… They saw images of Black soldiers coming from abroad from places like Germany and England, where Black soldiers were intermingling with whites and had a lot more freedom.” Charissa Threat, Associate Professor of History at Chapman University

“State employment agencies all across the country honored employer requests for whites only for many jobs." Richard Rothstein, author of The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America

Western Newspaper Union. “Colored Troops - Doing Kitchen Police on Board the Celtic.” 1917-1918. Retrieved from the National Archives Catalog

“If you’re an African American doing a good job, they’re going to find some loophole or exception to keep you from getting ahead." David Grogan, The Carolina Times

"...we have reached a turning point in the long history of our country's efforts to guarantee freedom and equality to all our citizens. Recent events in the United States and abroad have made us realize that it is more important today than ever before to insure that all Americans enjoy these rights. When I say all Americans I mean all Americans." Harry S. Truman, "Address Before the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People," 1947

“Truman Proclaims National Freedom Day.” July 1, 1948. Retrieved from the Bettmann Archive

“TRUMAN ORDERS END OF BIAS IN FORCES AND FEDERAL JOBS; ADDRESSES CONGRESS TODAY.” July 27, 1948. Retrieved from the The New York Times Archive

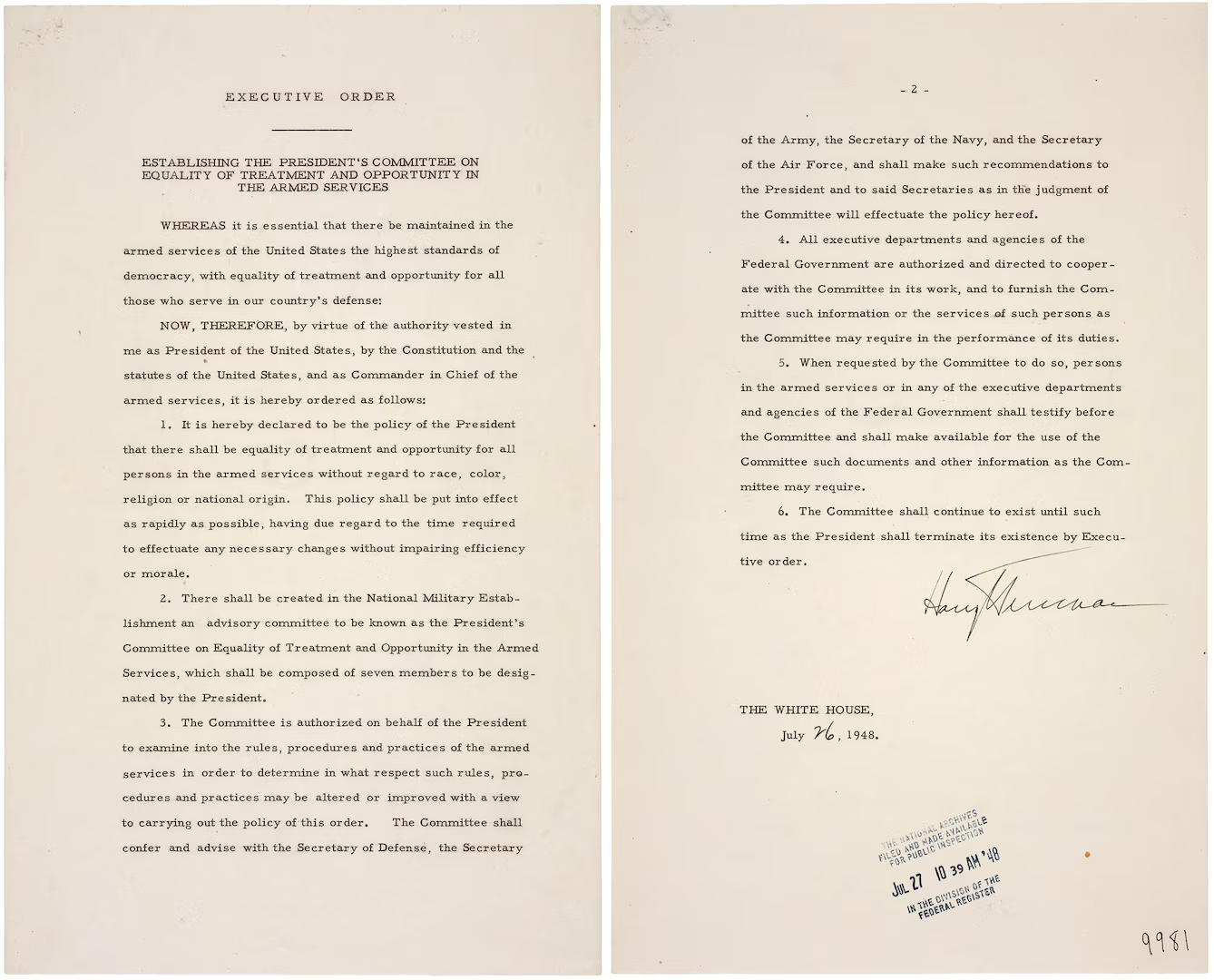

"Executive Order No. 9981: Ending military segregation," July 26, 1948. Retrieved from the National Guard Bureau

"Equality of Treatment and Opportunity"

"Truman decided to [sign Executive Order 9981] as reports of beatings and lynchings of Black veterans reached the Oval Office after World War II. He was especially moved by the blinding of Isaac Woodard, a uniformed Black soldier who was accosted by police in South Carolina just hours after an honorable discharge and beaten until his eyes failed forever." Theodore R. Johnson, The Washingon Post

Pressured by Black American civil rights leaders and reports of racial violence, President Harry Truman issued Executive Order 9981 in 1948, thereby ending segregation in the armed forces.

"In 1948, Randolph warned President Truman that if segregation in the armed forces was not abolished, mases [sic] of black citizens would refuse induction. Soon Executive Order 9981 was issued to comply with his demands." Winston-Salem Chronicle, 1982

Despite Executive Order 9981's implementation, integration faced intense opposition during the Korean War, the first partially integrated conflict. Systematic racism remained.

"Charles Rangel" May 28, 2013. Retrieved from the Korean War Legacy Foundation

"We had heard that the army was desegregated in 1948 by Executive Order from President Truman. I can assure you, by 1952, it [desegregation] did not get down to the troops at all. The only thing that was integrated, in the 2nd infantry division, were two units. It was the 3rd regiment of the ninth infantry division—they were all Black—and the 503rd field artillery battalion, which I was in, which was all Black." Korean War veteran and United States Representative Charles Rangel

"You still had white units, and black units. When I went to Korea the only white I had in my unit was a lieutenant… he was the company commander… 90 percent of all black units were commanded by white officers. And most of those officers… couldn’t make it in white units." Korean War veteran John Gragg