BRIDGING THE GAP

The Vietnam War: A Turning Point

for Black American Rights

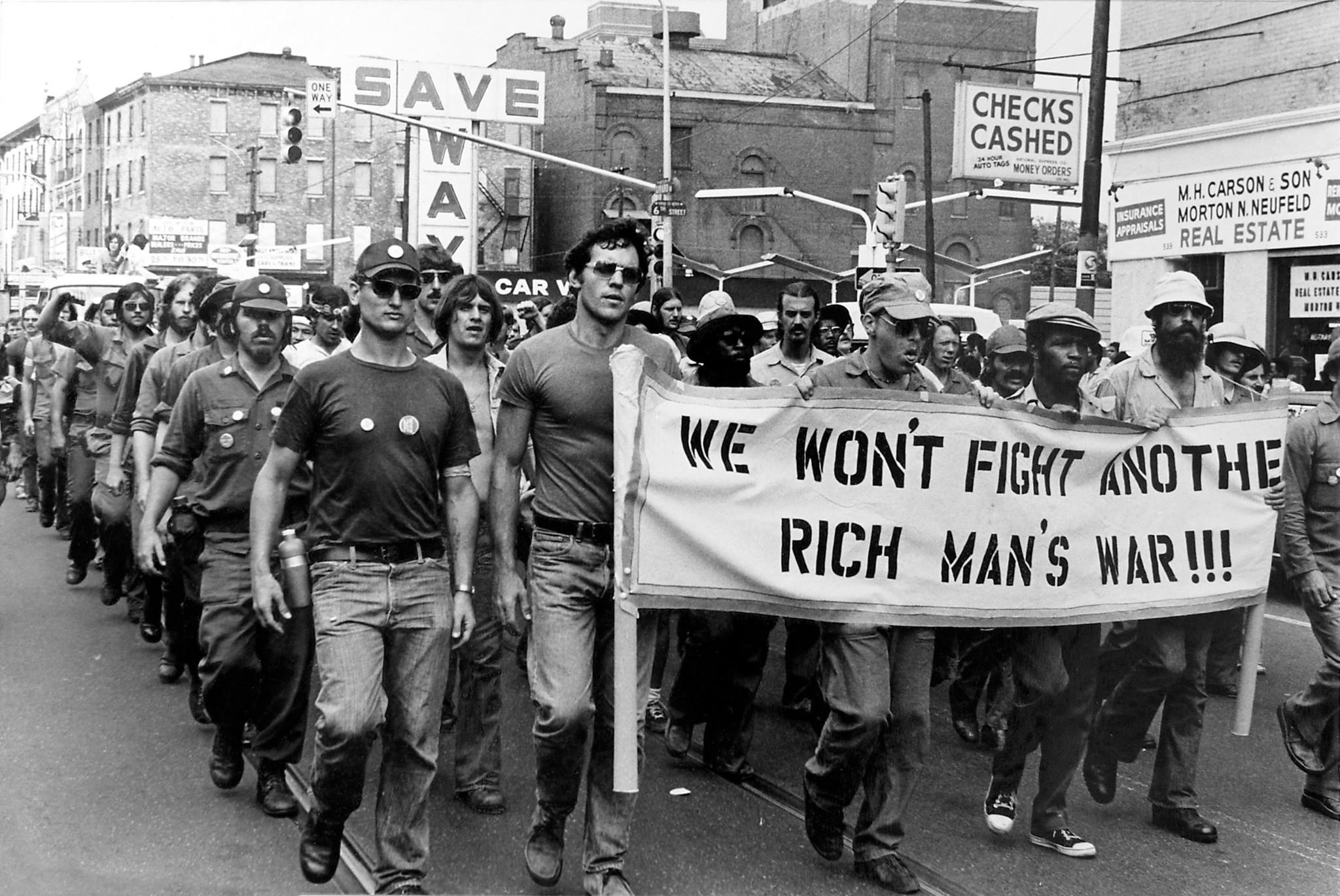

Joe Runci. "Protesters against the war in Vietnam hold up signs urging others to resist the draft and refuse to fight, during a demonstration in Boston on October 16, 1967." Retrieved from The Boston Globe

"And so we have been repeatedly faced with the cruel irony of watching Negro and white boys on TV screens as they kill and die together for a nation that has been unable to seat them together in the same schools. And so we watch them in brutal solidarity burning the huts of a poor village, but we realize that they would hardly live on the same block in Chicago." Martin Luther King Jr., Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence

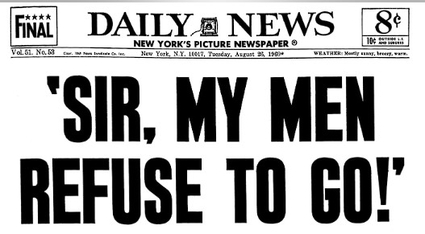

“Sir, my men refuse to go!”

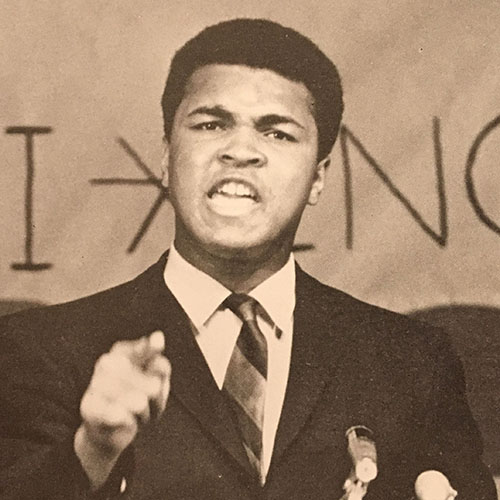

In 1966, Muhammad Ali, a heavyweight boxing champion, refused induction and failed mental exams to evade the draft. Nonetheless, the presence of the draft persisted, especially with Project 100,000 in place.

"Daily News Front Page" August 26, 1969 Retrieved from the New York Daily News

Muhammad Ali speaks at the University of Arkansas. 1969. Retrieved from the University of Arkansas

"Just take me to jail!"

“My conscience won't let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people, or some poor hungry people in the mud for big powerful America. And shoot them for what?” Muhammad Ali, 1967

As Ali's refusal garnered national attention, the media began highlighting the racial and economic disparities inherent in the draft system, prompting a growing number of Black Americans to question the draft and the broader war effort.

"We believe the United States government has been deceptive in its claims of concern for the freedom of the Vietnamese people, just as the government has been deceptive in claiming concern for the freedom of colored people in other countries as the Dominican Republic, the Congo, South Africa, Rhodesia, and in the United States itself." Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, SNCC Statement on Vietnam, 1966

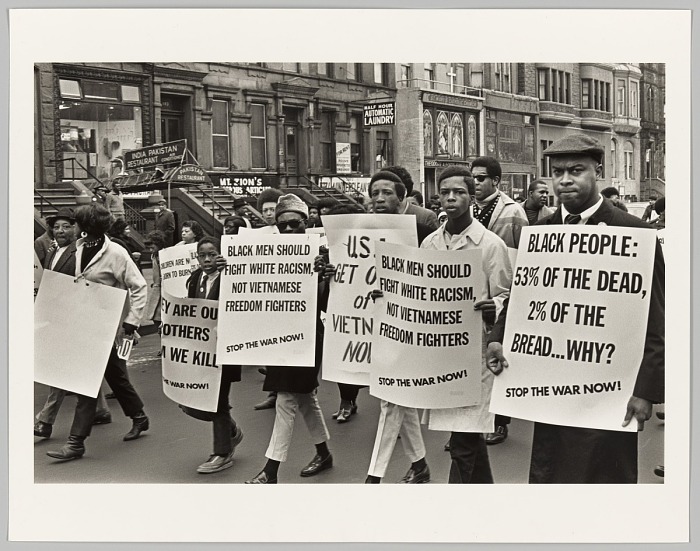

Protests exploded across the country, with Black students joining the efforts. Black soldiers serving in Vietnam also offered their distinct reactions to military service and combat, reflected in the significant decline of Black reenlistment rates, dropping from 66.5% in 1967 to 31.7% in 1968 (Phillips 2012).

Builder Levy. Harlem Peace March.” April 15, 1967. Retrieved from the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture

"Student Anti-vietnam Rally" November 5, 1968. Retrieved from the Bettmann Archive

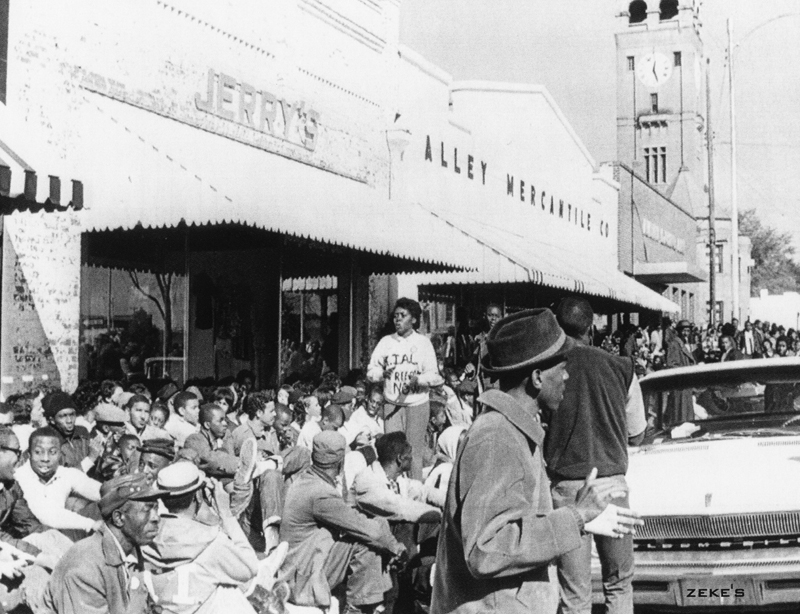

"People protesting the murder of Sammy Younge and SNCC's Statement on Vietnam" January 1966. Retrieved from SNCC Digital Gateway

“[A] new breed of Black soldier [had] arrived. Younger, with an average age of 18–19 years old, more aggressive, more militant, more confident." Chicago Defender correspondent Ethel Payne

"Let your mother do it."

Within the military, Black Americans engaged in acts of daily resistance. As early as the spring of 1967, reports emerged in the press suggesting that Black soldiers were refusing to fight, even alleging that Black soldiers shot officers who exhibited prejudiced behavior.

"The strongest and most militant resisters were black GIs. Of all the soldiers of the Vietnam era, black and other minority GIs were consistently the most active in their opposition to the war and military injustice." Vietnam War veteran David Cortwright, "Black GI Resistance During the Vietnam War"

“Veterans protesting war.” June 1, 1967. Retrieved from Zinn Education Project

Dignity and Pride

With more soldiers entering Vietnam through troop escalation, Black Americans responded to racist incidents and the uncertainties of combat with a newfound racial pride brought by the Black Power Movement.

Refusing to use deferential military salutes, Black soldiers opted for the handshake, the dap (“dignity and pride”).

"Many commanders considered the dap and the abandonment of military deference as a display of mass insubordination; others saw it as a sign of racial militancy; others considered it nonsensical and disruptive. When commanders attempted to restrict or ban the dap, blacks responded through resisting the order or rioted." Kimberly L. Phillips, Professor of History and American studies at College of William & Mary, "War! What Is It Good For? Black Freedom Struggles From World War II to Iraq"

“Off-duty at Chu Lai, African American Marines offer Black Power salutes at an outdoor bar that caters predominantly to them.” Retrieved from The Vietnam War: An Intimate History

Wallace Terry. “Soldiers in Vietnam do the ‘dap,’ a stylized greeting used to signify a shared black culture and racial unity,” 1969. Retrieved from Adrien E. Miller

White leaders also believed that Black Americans were unsuited for combat. Black Americans were promoted at lower rates than their white counterparts; even during promotions, they encountered bigotry from white soldiers ranked lower than them.

"Part of the thing I found to be true, both in the Air Force and civilian life — being a Black person, you can’t just be good. You’ve got to be the best." Vietnam War veteran Edward Morast

A Trigger of Racial Hostility

In April 1968, Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassination plunged Black communities into mourning and became a trigger of racial hostility in the military. White soldiers publicly celebrated his death, leading to riots.

“When I heard that Martin Luther King was assassinated, my first inclination was to run out and punch the first white guy I saw. I was very hurt… I didn’t understand how I could be trying to protect foreigners in their country with the possibility of losing my life, wherein in my own country people who are my hero, like Martin Luther King, can’t even walk the streets in a safe manner.” Black American Vietnam War veteran Robert Heinlein

From News Dispatches. "Dr. King is Slain in Memphis" April 5, 1968. Retrieved from The Washington Post

At the same time, engaging in warzone activity forced Black and white soldiers to collaborate since their lives relied on mutual support.

"Black-white relationships were reported to be better in Vietnam than in the U.S., especially among soldiers who served in actual combat. Blacks reported less negative attitudes toward the Vietnamese than did whites." Black-White and American-Vietnamese Relations among Soldiers in Vietnam

"U.S. soldiers and veterans who opposed the war" Retrieved from the University of Arkansas

“I had a white guy in the team. He was a Klan member. He was from Arkansas... And never seen a black man before in his entire life. He never knew why he hated Black people. I was the first Black man he had really ever sat down and had a decent conversation with…. And once you started to go in the field with an individual, no matter what his ethnic background is or what his ideals, you start to depend on that person to cover your ass.” Vietnam War veteran Arthur E. "Gene" Woodley, Jr.