CROSSROADS OF PROSPERITY

The Vietnam War: A Turning Point for

Black American Rights

The integrated special operations force unit, Tiger Force. Circa 1968. Retrieved from The Vietnam War: An Intimate History

"I was the first person in my family to finish high school. This was 1963. I knew I couldn’t go to college because my folks couldn’t afford it. I only weighed 117 pounds, and nobody’s gonna hire me to work for them. So the only thing left to do was go into the service." Vietnam War veteran Reginald "Maliks" Edwards

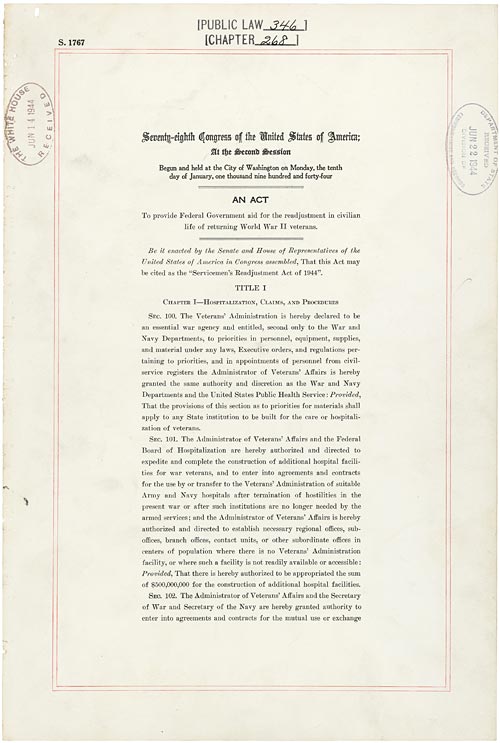

"Servicemen's Readjustment Act," also known as the G.I. Bill. June 22, 1944. Retrieved from the National Archives and Records Administration

The Path to Upward Mobility

The newly integrated military was a symbol of civil rights triumph for Black Americans, and in a time of limited economic and social opportunities, Black Americans joined the military for personal advancement and racial activism.

“[B]lack men who couldn’t find jobs otherwise gravitated to the services because [war] did provide employment opportunity.” Chicago Defender correspondent Ethel Payne

With the G.I. Bill of 1943 offering education funding, business loans, and property assistance for veterans, the military became the sole and appealing choice for many—but even then, the G.I. Bill's opportunities were scarce for Black Americans.

“In New York and the northern New Jersey suburbs, fewer than 100 of the 67,000 mortgages insured by the GI bill supported home purchases by non-whites.” Ira Katznelson, Professor of Political Science and History at Columbia University, author of When Affirmative Action was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-century America

McNamara’s Morons

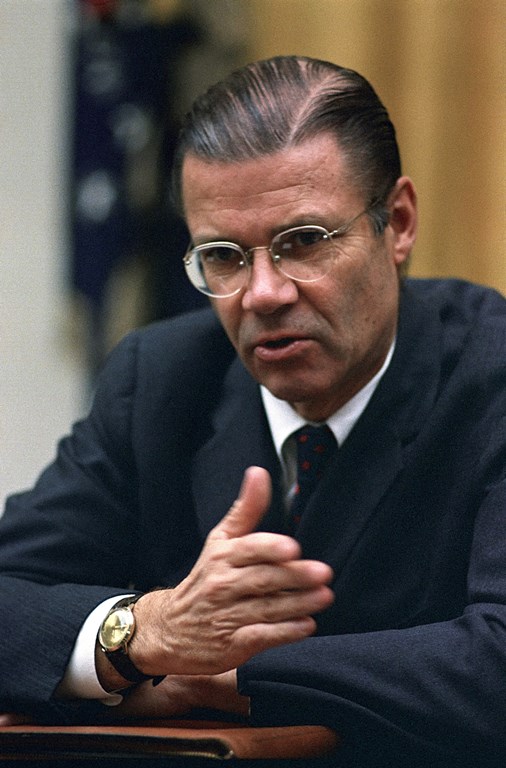

In October 1966, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara launched Project 100,000 to recruit individuals below military standards. Over the first three years, about 40% of those filtered were southern Black Americans.

"A total of 5,478 low-IQ men died while in the service, most of them in combat. Their fatality rate was three times as high as that of other GIs. An estimated 20,270 were wounded, and some were permanently disabled (including an estimated 500 amputees)." Hamilton Gregory, author of McNamara's Folly: The Use of Low-IQ Troops in the Vietnam War

Though Project 100,000 would end in 1972, its participants, compared to non-veteran peers, exhibited lower employment rates, educational attainment, and incomes.

"[T]hey talked too loud and made too much noise while moving around, didn’t know what to take into the bush or even how to wear it properly, couldn’t respond to basic combat commands, fired too much ammo, and tended to flake out on even the easiest 10-klick [kilometer] moves." Anonymous Vietnam War veteran, Task & Purpose

Robert McNamara. Retrieved from the 50th Anniversary of the Vietnam War Commemoration

"A white man's war, a Black man's fight." Martin Luther King Jr.

Local draft boards disproportionately drafted Black Americans, with only 1.3% of board members being Black in 1966. These boards favored white males with connections, granting exemptions for medical issues and university enrollment (Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund).

Despite constituting just 11% of the population, Black Americans made up 23% of Vietnam combat troops (Time 2020).

In 1967, 64% of eligible Black American men were drafted, compared to 31% of eligible white men (Phillips 2012).

"First we provide an inferior education for black students. Next we give them a series of tests which many will flunk because of an inferior education. Then we will pack these academic failures off to Vietnam to be killed." United States Representative Adam Clayton Powell Jr.

Black Americans even volunteered to enter the war on the condition that they would not enter Vietnam, but they were still assigned to Vietnam.

"The sergeant—he had told me... if I take another year that I would have the opportunity to get the type of technical training that I wanted, what area field I wanted to go into. That if I take another year also it would assure that I would not go to Vietnam... I received my orders and my orders said Vietnam." Vietnam War veteran Phillip Key

"A military funeral in a small South Carolina town, 1966." 1966. Retrieved from The Vietnam War: An Intimate History

Interview with Philip Key. July 15, 1981. Retrieved from Open Vault